The Math of Motherhood: The Motherhood Penalty

on what we really sacrifice when we become mothers

The above is a graph from a 2024 article in The Economist titled “How Motherhood Hurts Careers.” It shows the sharp drop in employment for mothers upon the birth of their first child and how long that lingers. Due to lack of paid family leave combined with lack of affordable childcare, many mothers leave the workforce because there is just no other option.

We know the dire stats. Less than 30% of employees in the U.S. have access to any leave benefits. To have a child and keep your job, you must save up vacation days and sick days. That might get you to your child being three weeks old. Most childcare centers will not take an infant who is less than six weeks old.

Fathers don’t seem willing to step in and provide care. For those fathers who do take time off when their child is born, 76% return to work less than a week after. This is even when they received paternity leave. But they don’t take it. Why? 44% of fathers said using their leave could affect their performance reviews.

Because fathers won’t allow their careers to take a hit, where does that leave us? With mothers taking one for the team.

But stepping out of the workforce has long term consequences not just on your career but on your lifetime earnings. Women who take one year off work upon the birth of their child earn 39% less than those who stay in the workforce.

It turns out the gender pay gap is really about the motherhood pay gap. Take this fact: A college educated woman in her 20’s makes 90% of what her male peers earn. But a college educated woman in her 40’s makes 55% of what her male peers earn.1

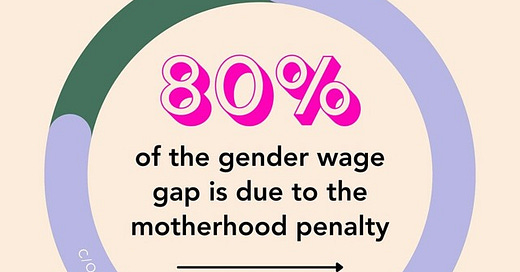

This has frequently been called “the motherhood penalty.” It accounts for the fact that mothers, even if they stay employed upon the birth of their child, receive a cut in pay. They are less likely to receive raises and promotions because societal bias means we expect that mothers will be less dedicated to their careers.

The motherhood penalty hits even before you become a mother. If you are of the age where you might become a mother, employers will discriminate against you, giving the job to someone who is not likely to become a mother during their tenure at the company, or offering lower pay due to the expectation that motherhood could impact your dedication to your career.

In order to shift this societal bias, we must begin to see caretaking work as the work of men, not just women.

I have written about why paternity leave is so important in the post below. Because if dads aren’t willing to show up as caregivers upon the birth of their children, this bias will continue.

“When fathers refuse to take the full time offered them, it does a disservice to our attempts to create a more equal workplace. If mothers have to be the ones at home tending to newborns because fathers refuse to be seen prioritizing care over career, managers will be less likely to hire women in anticipation of this potential motherhood (it is called maternal bias). When we share this kind of caretaking equally among all genders, there can be no motherhood penalty because the expectation and norm is that both parents take time off to care for their children.

When men don’t take paternity leave or only take two weeks, it signals to the world who the “real” parent is… Mom. And we all know that that messaging continues for the rest of our parenting journey. Who gets called by the school? Who gets texts about playdates? Who is responsible for keeping track of the mental load? It all starts here. If we want more to be expected of dads, we need to signal their essential role from the start.”

Now, let’s get into the numbers.

In this Fortune magazine story, Chloe Berger reports that a first born child has no effect on a father’s pay, while moms experience a 51% dock in their pay, or an average of $8k annually.

In this article from Australia, it reports that “the average 25 year-old woman who goes on to have one child can expect to make $2M less in lifetime earnings compared to a 25–year-old man who becomes a parent.”

Another report: a mother makes 58 cents for every dollar paid to fathers.

Let’s do a math exercise. Let’s say this is one couple. The mother makes $58,000 a year doing the same job for which the father earns $100,000. That is $42,000 per year she misses out on. Say they became parents when they were 30 years old. Even if their pay didn’t change at all over the next 30 years, $42,000 x 30 years = $1,260,000 less income for the mother.

And of course this father would likely receive additional raises and promotions, being seen as more dedicated to his job upon fatherhood, so you can see how that could become $2M. (This is called The Fatherhood Bonus).

This is IF the mother stays in the workforce. If she takes time off, she is even worse off.

These issues have long-term ramifications for what women are able to save for retirement and their lifetime wealth accumulation.

In this article on “The Hidden Costs of Unpaid Caregiving” in The Washington Post, they report that mothers have $295,000 less in retirement savings than men. Stephanie Murray explains how this can happen in The Atlantic: “America’s primary safety net for the elderly - Social Security - rewards long careers and high pay, all but guaranteeing that parents who focus on the work of childrearing receive the smallest payouts.” She continues: “When you retire, the amount you receive in Social Security each month is a percentage of your average income during your 35 highest-earning years…By design, this system penalizes anyone who, at any point in their life, works part-time; chooses a lower-paying, family-friendly job; or stays home to take care of their children. Because women are more likely to do all of those things, they inevitably receive smaller payouts than men. The average retirement benefit for men is about $1600 a month, roughly $300 more than the average woman receives.”

Now, if this couple stays married, they will be able to share in those retirement savings. But what if they get divorced? As I have written about here, spousal support is not mandatory. Many men, when they go through a divorce and their spouse has taken time out of the workforce to care for children, argue that it was their spouse’s choice. They then expect said ex-wife to go out and get hired immediately, despite the gaps in her resume. They don’t want to have to pay for her living expenses while she tries to find a job that covers her bills. But a study published in 2018 showed that stay-at-home moms were 50% less likely to get an interview than women who were laid off from their previous jobs.

Harvard Business School calls this the challenge of “on-ramps.” Once women take an off-ramp for their career to deal with caretaking needs, it is much harder to get back on their previous career trajectory. Research from 2022 shows that women are five to eight times more likely to have their careers affected by caregiving than men. In a study that is admittedly dated (2005), HBS reports than 1 in 3 women with MBAs were not working full-time compared to 1 in 20 men with MBAs. When women take an off ramp, they lose 18% of their earning power. If they are out of the workforce for more than three years, they lose 37% of their earning power.

Again, if you are able to stay married to your partner, you won’t feel these economic realties so acutely. But if you are one of the 50% of couples who get divorced, you will find these issues brought into stark relief. You will face a future where you are the sole earner, but your earning power has diminished forever.

If you take a step back in your career for your family, you are putting yourself in a vulnerable state. And every financial advisor I’ve spoken to has been frank: Don’t do it. Don’t step out of the workforce. Ever. At all.

Now, sometimes this math can get a bit more complicated. For example, when I stepped out of the full-time workforce, I began a freelance career, like many mothers. They decide not to stop work all together but to try and take their skills and turn them into something they can bill for hourly, on the side, when not caretaking the children. I was able to make more working part-time than I was making full-time at my job in publishing after two years. But, this was not steady work. This was not salaried work. It provided no health benefits. There was no 401k matching. I did not get promoted or receive raises. It was contract work. Sporadic. Not something that you could depend on.

Some women decide to use their off-ramps to build their own companies, becoming entrepreneurs. And again, sometimes this works out for them. But many times, it doesn’t pay off and then they try and jump back into the workforce but given the gap in their resume, they are not able to get hired at the level they would have if they had not stepped away.

Our hand is forced until we have paid family leave and affordable child care. We have neither in our country right now. But certainly don’t make the mistake of factoring in only your salary when determining whether child care costs more than you make. It should be your salary plus your spouse’s salary minus child care costs.

If you want to step out of the workforce to care for your children, that is of course your choice. But couples should be having frank discussions about how caregiving decisions impact long-term career goals and earnings potential. In The Math of Motherhood: Pregnancy Edition, I referred to a conversation on Reddit about whether a woman’s partner (they were not married) should compensate her for giving birth to their child and the subsequent time she would take off work. She was a high earner and lived in a country where her employer provided partially paid leave for a year. She was asking her partner to compensate her for the lost earnings she would sacrifice if she had the child and took that year off work. It amounted to about $50,000. He of course thought it was gauche that she ask to be compensated for having their child. But her request was fair. They kept their finances separate and paid their bills 50/50. He would go on to earn his normal salary the year she gave birth, while she would not.

This is one of the reasons that I’ve been considering the importance of post-nuptial agreements if one partner takes a step back to care for children. There should be a stipulation for spousal support upon divorce if a career was sacrificed. That post is forthcoming, but in the meantime, we cannot just keep allowing men to earn unencumbered while women take the hit. As this American Progress report states: “Plateauing of women’s earnings relatively early in their careers has serious ramifications for economic security over the life course. Men whose earnings grow decade after decade are better positioned to save for retirement…and engage in other forms of savings.”

Sometimes I wonder if our apathy about this issue is because society still feels like money is the purview of men. Women are not taught to pursue high paying careers, to seek wealth, to talk about money, to ask for raises. What I find over and over in divorce land is people asking me what will be “enough.” Like, what will be enough for you to be able to walk away and be done? What will be enough for you to feel secure? Meanwhile, I don’t see anyone asking my ex that. It is assumed that he will be able to continue to be wealthy, while I am expected to just “get by.”

This infuriates me, of course, because he is a high earner thanks to my support (for more on this issue, read my post on Wifedom). I downshifted my career to part-time upon the birth of children and stayed part-time until the pandemic at which point I quit altogether. That is 9 years of part-time work followed by several years of no earnings. In addition, during this time I volunteered at our pre-school, making our pre-school tuition essentially $0. If you want to examine how much money I saved our family during those years, read The Math of Motherhood: Unpaid Labor edition.

Women should not make less than men. The fact that we still do so is astonishing. Yet until we have policies for family leave and subsidized childcare, the motherhood penalty will exist. Until we have fathers who are willing to have their career impacted by fatherhood, the motherhood penalty will exist. Until we have spouses who are willing to do their fair share at home, the motherhood penalty will exist.

GOING FURTHER

Tori Dunlap, The Financial Feminist Podcast.

Thanks to The Fifth Trimester for her stellar opening graphic and all her work

and her Substack The PurseThe Gender Pay Gap Is Largely Because of Motherhood. The New York Times. Claudia Cain Miller.

Great article. It is outrageous the conditions you have to put up with in the US. I read the stat about only 30% of workers getting paid leave over and over because I just couldn’t comprehend it.

I notice some of your data is from Australia, where I am. We have paid parental leave and subsidised childcare and the motherhood penalty is still really bad here. Obviously the US needs that as an absolute baseline but it is not a panacea.

I feel like you know this based on my reading of your article, but until we start to see childcare and raising children as a shared responsibility not just for mothers, and money being for women as well as men, this is never going to change.

It’s funny, I’ve been saying for a while, half jokingly, that we need mandatory paternity leave if we want equality. Not mandatory it’s offered, mandatory that men take it.

I’m fortunate to find myself in a management position these days and I always make a point to let my staff know that when we had our kids, both my wife and myself took 3 months of leave. Partly that’s so they have the expectation that it’s ok for them to do so, male or female, and partly because a lot of the time folks don’t think of how flexibly this can be done. We are fortunate to live in New Jersey, where paid leave, 3 months for each parent, is now law (although sadly it’s only 60% salary). But you can also take that time at any point in the first year, and it doesn’t need to be in one chunk. My wife took off 2 months initially (using disability after birth meant she could take more than 3 months total), while I returned to work after 2 weeks. She then returned to work 3 days a week, while I worked 2 days a week, and that allowed us have our son home until he was 6 months old, and meant we were both present in the office for most of that period, just to a lesser degree.

A lot of the time I think folks don’t realize that’s an option (and, to be fair, throughout much of the US it isn’t). It’s absolutely important for men to show that this kind of thing can be done, and also for management to not only make sure their employees are aware they’ll be supported on leave, but also to walk the walk if it’s them who’re being the carers.