Lately I’ve been reflecting on the importance of language. What we say matters and what words we use impacts how we feel. For example, the push back against the terms “geriatric” pregnancy and “incompetent” cervix, misogynist words designed to make women feel bad.

Another term I have long found troubling is “stay-at-home mom.” What does that even mean? What parent “stays home” with their kid? Most of the time, I felt like, once the kid was mobile, it was about getting them OUT of the house, so that we felt like we were a part of the world. The four walls of the home can feel very confining when sequestered with small children.

Before “stay-at-home” mom, women who didn’t work outside of the home were called homemakers, and before that, “housewives.” While I’m glad those phrases are no longer in fashion, we still don’t have the right solution (check out this article from 10 years ago regarding this problem).

You could call yourself a “full-time” mom but that implies that “working moms” (another loaded term) clock out of their motherhood role once they leave the house and anyone who has ever been a mother who works outside the home knows that is not true.

Stay-at-home is such a weird phrase because it is focused on location rather than job. It signals being in the house (which you often are when the infant is small) rather than what you are actually doing, which is caretaking, household managing, cleaning, cooking, running out to Target, Costco, the grocery store, the dentist. A more accurate term would be “on-the-go” mom. “Always-rushing-off-to-something” mom. “A-slave-to-other-people’s-schedules” mom.

I had the chance to meet Shannon Carpenter, author of The Ultimate Stay-at-Home Dad at AWP this March. He was on a panel on caregiving and it was so refreshing to see a male up front talking about the work of parenting. I introduced myself afterwards as I sensed that his perspective could be helpful as I tried to keep this Substack from falling into gendered assumptions (perhaps it is too late?!?!).

We were emailing a couple of weeks ago and I asked him how he handled the long months of summer with no childcare. And he used this phrase. He said: “Remember, I’m a professional dad…” and then he went on to describe all the things he does with his children (and emphasized that he tries to do things HE enjoys and then gets his kids involved in them).

But that phrase “professional dad” stuck out to me. What would it feel like if moms who “stayed home” with their children, called themselves “professional moms?”

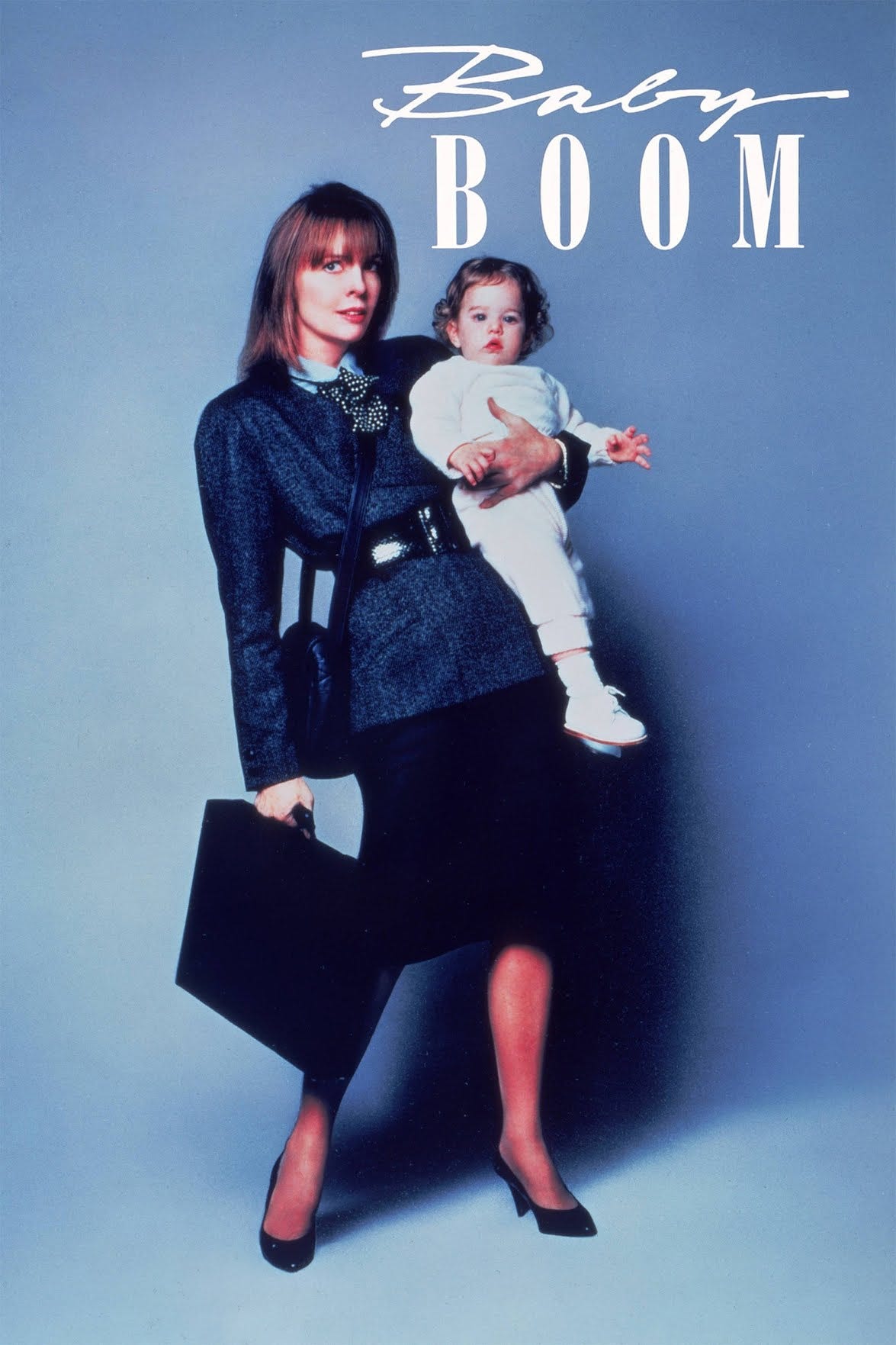

Unfortunately, when I hear the term “professional mom” I think of mothers in the workforce, ala Diane Keaton in “Baby Boom.” I think the term “professional mom” inherently means something different than “professional dad.” But if we put aside the pictures in our minds of moms in skirt suits and Reeboks kissing their kids before heading to their corporate offices, what might emerge?

What I like about the term is that it emphasizes that parenting is a job. It is something that other people would be paid to do if you were not doing it.

Now, I’m sure when Shannon says he is a “professional dad” he receives smiles and high fives. Good for you, dude! Because being a professional dad is an anomaly, a bucking of the system, and men are allowed to claim things women are not. Would women get the same reaction? Likely, they might receive eyerolls. Like, okay, girl, if you really want to take yourself that seriously. Professional mom, who is she kidding? She’s just a mom! This would probably be from women as well as men. Our misogyny runs deep.

We still socialize women and men to expect that women who take on the role of primary parent and house manager are lucky. Watch this TikTok in which the poster eviscerates the idea that staying at home with your children is a privilege. “How did we allow men to rebrand cooking, cleaning, taking care of kids, dropping them off and picking them up from school…as a privilege?” she asks as she records her video while clearly pushing a stroller.

No, the work of parenting is labor. I’ve been reflecting on this concept a lot. (See The Math of Motherhood, Episode 2). In a comment on social media on The Infantilizing of Men, someone suggested that one solution to men claiming incompetence is that we bring back Home Economics classes, but only for men. I thought it was an intriguing idea but would argue that the class should be for all genders. Some of the problem stems from the fact that we assume caretaking and home maintenance comes “naturally” to women, when cooking and cleaning and nurturing are skills any adult should learn. And by putting it back in classrooms, might it suggest once again that this is work, that it has value? That it is a skill that is cultivated, not something that you just inherently know?

Until the pandemic, I was not a “stay-at-home” mom. I was a mom who worked part time while her kids were with other people. So I am not sure I would have felt comfortable claiming the title “professional mom” because I was still trying to be something else, a writer, who brought in a paycheck, while simultaneously trying to give my children the kind of childhood where they felt like they had a stay-at-home mom. I was a hybrid mom. I was their primary caretaker, but also tried to cultivate a career. Yet I never hired a nanny. My children were never enrolled in a day care. I don’t say this to brag. I say this to show how much I tried to be something I was not (a “professional mom?”). My children went to mom’s house for a few hours or to preschool for a few hours, or sometimes a babysitter would come for a couple hours in the afternoon. I don’t think I was separated from my children for more than four hours at a time during the work week until they each went to kindergarten.

I think a lot of mothers try to do this. They scale back their careers so they can be around for their kids (or due to lack of childcare) but they keep this small pocket of their life for their work. But it is a hidden pocket. It can’t get too large or be too disruptive or it all breaks down (let me tell you, one day, about the ghostwriting project that required me to be in West Palm Beach, Florida for several days at a time. I live in California.).

“The sense of entrapment I feel is not Pete’s fault, but I want to blame someone and he is the only person I can, apart from myself….Being a mother at home who does freelance work in the cracks of time in between the school gate, swimming lessons and mealtimes has made me angry.”—Clover Stroud, My Wild and Sleepless Nights

The bottom line is, I don’t know that many women who want to be “professional moms.” Is that because it is still such an undervalued role? Is it because we are waiting until later to become moms and no longer want to put the careers that we’ve built on hold? Is it because, maybe, just maybe, we didn’t really want to become moms but did so because that is what our society pitched as a sign you’ve succeeded in life as a woman? Is it because we don’t want to find ourselves in a powerless position if our marriages fall apart and we suddenly need to find a way to bring in income?

“Did my children see their father’s job as more ‘real’ than mine because it happened outside the home, and because despite my work, I was the primary caregiver? I felt that he treated my (writing) work like an interruption of my (domestic) work, and did they see that, too? When I traveled, I planned carefully for minimal disruption to his schedule. I arranged playdates for afterschool or asked my parents for help. But I couldn’t pack lunches ahead, give baths ahead, make breakfasts ahead….I didn’t feel missed as a person, I felt missed as staff.”—Maggie Smith, You Could Make This Place Beautiful

So, if you are a parent who is the primary caretaker, what do you think of the term “professional parent?” Do you like that reframe, or does it still not encapsulate what you do, who you are, the sacrifices you make for your family? Because I do think that giving up a paid career is a sacrifice, and one we should not belittle. It is significant to quit your job and become a primary caretaker for years, fitting in work projects on the side that bring in income, yes, but not enough to consider yourself the breadwinner in the family. It is a sacrifice to only have small pockets of time in which to do said work, being constantly at the whims of when schools are closed, or release early, or winter and summer vacations, or when your kid gets sick. It is a sacrifice to be the one who does all the night wakings because you don’t have a “job” to clock in for the next day.

It is a gift you give your spouse to be able to work unhindered, 365 days a year.

Now, I recognize there is a flip side. It is also a gift to not have to worry about money coming in. To have that taken off your plate completely. I recognize that providing financially for your family is no small burden. But you get compensated for that work. It is dollars that go into a bank account, and no matter how quickly they get removed, it is something tangible. There is money that I earned.

That is denied to a person who sacrifices their career and spends their days doing tasks that get erased almost as soon as they are completed.

So what is the solution? Could we come up with a term that made the job of caretaking less thankless? That honored what we do as labor, in addition to love?

Asking for a friend.

FURTHER READING:

I’m a huge fan of The Matriarchy Report on Substack. I suggest Women Need Their Own Damn Money, and On quiet-quitting American adulting and having more fun. You can subscribe to their newsletter here.

“Risks to Mothers’ Health Lasts a Year After Childbirth.” The New York Times published this important piece on risks to mothers in the year after childbirth on Sunday.

Loving this excerpt from Sara Sadek’s recent Substack:

“If we picture a web of care holding my daughter up, our web looked like a very thick chord connecting my elder and me, a sliver of a chord between her and my partner, a sliver of a chord to a babysitter who would come three hours a week, and until she was about two years old, that was it. Those were all the adults she could safely lean into.

That is a seismic load for one person, and does not lend itself to a particularly resourced mother, which we need to be to provide attuned attachment. Nor does it do anything to protect a mother’s liberation. Instead, it reinforces regressive gender dynamics that keep partners from stepping in as capable caregivers, reinforcing a negative feedback loop that keeps a partner’s thread thin and a mother’s attachment chord even more robust and therefore even more heavy.”—Sara Sadek, on Radical Matriarch

Lessons from a Renter’s Utopia. Finally, this article in The New York Times Magazine about subsidized housing in Vienna and how little of their paycheck goes toward housing is so unreal. What would happen if we all didn’t have to work so hard to afford a roof over our heads? What would open up in terms of opportunities and enjoyment of life?

And thank you for sharing a bit from my piece on here. I'm glad it resonated.

Cindy--what an important inquiry. the language we use matters so much, and stay-at-home is literally confining us with language. What about "I'm a mother" said with groundedness and power? Do we need the professional piece there, or can we just reclaim the value of the word in the saying it powerfully?

I was talking with a friend about a similarly-absent term for women who choose not to become mothers. All the language that exists is about them lacking in some way (kidfree, childless)--it all defines them for what they're not, not what they are. Definitely another one that needs an apt word, though I'm probably not the one to create that one!

I'm not a mother (yet, perhaps) but I feel like I'm preparing myself for the economic, physical, and mental hurdles of motherhood when reading your newsletter. Very thought provoking content!