For Mother’s Day, I wrote about the lack of postpartum care in America. But today, I want to explore a hallmark of postpartum care that I find deeply disturbing: the traditional six-week check up where the OBGYN gives the green light for parents to resume sexual activity. Lately, I’ve been thinking about how out of tune this timeline is with what a new mom needs. She does not need someone granting more access to her aching, exhausted body.

I know, I know. A doctor isn’t “granting access,” just assessing a mother’s health and recovery. Yet there is something inherent in the whole process that just feels off.

I’m not saying that if a new mother feels ready to resume her intimate relationship with her partner, she shouldn’t be allowed to. I’m suggesting that she should get a grace period where she gets to opt out. Then she is the one who decides when she is ready to resume those “wifely duties.” (Ugh, I’m so sorry, that sounds horrible, doesn’t it? Why did I write that? That was the patriarchy speaking through me. I don’t think sex should be a wifely duty, do you? Do you? More on this later.)

Anyway, I digress.

The practice of giving the green light for sex just six weeks after childbirth creates a dangerous dynamic between the partners (I recognize that for most of this post, I am assuming a heterosexual couple. I do not mean to be heteronormative). If the doctor says sex is okay, the husband thinks it shouldn’t be off the table. But for women who have just undergone childbirth, sex is often not only the farthest thing from their brain, but also triggering. The locus of “sex” is also the locus of the trauma of childbirth. How can you imagine pleasure coming from there? (Besides the fact that sex is the very act that placed you in your current state of servitude to a being that obliterates your ability to have a life of your own).

I think we should do away with the six-week green light. In fact, I don’t think doctors should be able to green light sex. Only the mother can do that.

Instead, what if the medical professional gave the mother permission to take a six-month hiatus from sex? Six months to get through the triage of healing their ravaged body and the hormonal avalanche of matrescence. Six months to dedicate just to their infant and themselves, no need to cater to another body’s needs.

Then, upon the six month mark, new mothers can check in with themselves and determine whether they are ready to reawaken their sexual self. In fact, what if we had rituals that welcomed us back into our bodies and allowed us to access our sexual energy again? It is all too easy to become divorced from our sexual selves in the fire hydrant of the infant’s needs, and because nothing about being a mother at home with a child feels sexy. Rather than the six-week checkup thumbs up, what if we honored the mother’s need to be “closed for business” for a while, and then had a process that allowed them to rekindle that side of them in a way that felt safe, good, and pleasurable in their new state of being?

Emily Nagoski writes about how important context is for women to be able to experience pleasure or desire. “When your brain is in a stressed state, almost everything is perceived as a potential threat…everything is a charging lion. And if you’re being chased by a lion, is that a good time to have sex?”

New moms are anxious; they have a new being under their care and that child’s survival depends on them doing things right. In addition, they are sleep deprived. Every moment they are not tending to the infant, they need to be restoring their deeply depleted reserves.

When men try to initiate intimate activity and women push them away, they do so because no part of their brain is ready to relax, to slip into a state of eros. They are thinking about all the things they need to accomplish in this small sliver of time when the infant isn’t needing something from them.

Add to the fact that in early motherhood, mothers can often become “touched out.” Amanda Montei wrote a wonderful piece on Slate about this: “The notion that women should sacrifice their bodies at the altar of parenting, and marriage, only extends and upholds the assumption that women’s bodies are made for the taking.”

Becca Maberly (@amothersplace) writes in the Instagram caption above: “I can’t be a mother and a lover!!” Though it is possible, the current state of motherhood certainly leads to us feeling overextended and under-supported. How is there any time to want sex?

As I mentioned in my last post, part of our lack of connection with our sexual selves is likely due to us being divorced from desire through our conditioning as women. As Esther Perel writes in Mating in Captivity, discussing a mother struggling with a lack of interest in sex: “We explore how she might reclaim a right to pleasure, with its inherent threat of selfishness….before she can open herself to sex, she needs to expand the general domain of personal pleasure. Becoming more generous with herself…”

Not all women struggle with the desire for sex post-childbirth. When I posted this discussion on Twitter, one OBGYN told me she had a patient who was ready for sex even in the hospital! Yet I think struggles with sex postpartum are much more common that we realize when the only thing we have for comparison is the six-week mark set by medical professionals (probably years ago and likely by men). Maberly asked her followers when their sex lives returned to normal post-childbirth, and a huge number of responses said after about a year, or around the 18 month mark. Many admitted that even years later, the new normal was sex about once per month.

For the most part we aren’t open about these experiences, thus mothers feel shame when they think everyone else is ready to jump back in the sack once the doctor okay’s it. But the reality is, sex is lower down the priority list by necessity. And what if there is nothing wrong with that?

“Maybe, I thought, the libido of a certain kind of woman is an animal that lives a little and then crawls into a cave and lies there panting for a few decades until, with a final ragged pant, it expires. Could it expire so early? Or perhaps it was taking a breather postpartum—understandable, surely, given how a six-and-a half-pound human body had been slither-pulled out of the place I get fucked, or one of the places.”—Jean Garnett, “Scenes from an Open Marriage,” The Paris Review

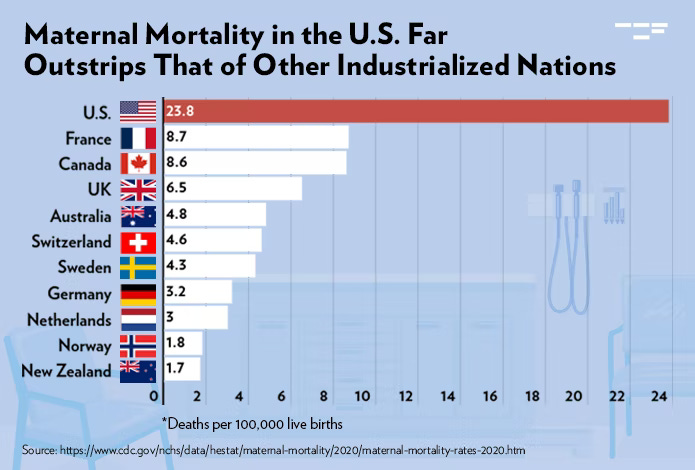

As Diane di Prima writes, sex is a dangerous act for a woman. In Recollections of My Life as a Woman, she writes: “Every chance sexual encounter was weighed: was it worth, ultimately, dying for, if it came to that?” I wish that was no longer a true statement but given our maternal mortality rate in this country, and our diminishing access to abortion, it is still a relevant question. The act of penetrative sex is what placed us in these shackles of motherhood so perhaps we cower in the face of it, not wanting to be subjected again to the state of imprisonment. We are often not yet on birth control until a year postpartum, due to the fact that it can affect milk supply if you are breastfeeding (and now the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends breastfeeding for two years). So each act of intimacy is a potential pregnancy.

If we could recenter the focus of heterosexual sex from the phallus to the woman’s body, perhaps we could avoid some of these issues. If during the postpartum period, after that six-month hiatus, we could reflect less on a man’s entitlement to sex, and more on how to reawaken the sexual self buried under the demands of new motherhood, we might avoid some of these dilemmas.

What if postpartum sex was by definition, different?

Sex as an invitation to connect, rather than a desire to “get off.”

Sex focused on giving the mother something, instead of depleting her reserves even more.

Tenderness as the rule, and penetration always optional, a form of sex that you can choose instead of the expected avenue.

Sex as worship of the female body and what it has accomplished and been through; reverence instead of ravishing.

What I find so difficult in the whole postpartum sex debate is the trope of the panting, impatient husband waiting in the wings. The problem is that we still have this idea floating in our consciousness that husbands are entitled to sex. In fact, I think that’s where that horrible phrase (“wifely duties”) emerged in the beginning of this piece. It wasn’t until 1993 (yes, 1993!) that it finally became illegal in all fifty states for a husband to rape his wife.

The entire idea that a wife should submit to her husband, prevalent still in conversative Christian circles, inadvertently can be interpreted as submitting to his sexual needs. Shockingly, Maberly reported that, in an Instagram poll in response to the question: “Do you have sex sometimes because you feel like you should?” 60% of respondents (assumingly women) said yes.

Perhaps because we lack boundaries with our children, feel we can’t say no to their hands constantly reaching out like addicts, we stop saying no to our partners as well. It is just one more taking, one more way our bodies become vehicles for other’s pleasure, rather than our own.

Truly, this is a conversation about consent. Koren Zailckas writes in Glamour: “Anytime we keep quiet and prioritize a man’s desires over our own, we are aiding and abetting a world where men don’t have to practice empathy or even be aware of their privilege.” And Emily Nagoski states: “Sex is not a drive, it is not a ‘biological need’ and no one is entitled to it.”

But I think we are still coming to terms with this truth in our society (as the #MeToo movement testifies). Deep down, do we still think “boys will be boys,” excuse bad behavior and demands to their testosterone levels?

“I needed my body honored for what it was. What it had become…for its status as community property; it was no longer mine now, a private preserve, but there for the kid to climb on whenever she could. That one fact alone changed me - that I truly did not own my physical self.”—Diane di Prima, Recollections of My Life as a Woman

We cannot ignore that women do not feel a true ownership of their bodies in the early days of motherhood. It is impossible to feel autonomy over your body when it makes food on demand for someone else. Even if you choose not to breastfeed, the constant vigilance that a mother experiences when her baby is sleeping and could wake at any moment is its own kind of hijacking.

So let’s just give new mothers a break, shall we? Let’s not expect them to slip back into their sexual selves in the midst of matrescence. Let’s allow them to be their own authority over when they are ready to re-enter the ring. And it is likely not when their infant is six-weeks old.

RECOMMENDED READING:

I Spent My Life Consenting to Touch I Didn’t Want. Melissa Febos. The New York Times Magazine.

How American Moms Got Touched Out. Amanda Montei. Slate.

The Woodpecker. Annie Marhefka. Literary Mama.