“Some women make it look so easy, the way they cast ambition off like an expensive coat that no longer fits.”

—Jenny Offill, The Dept. of Speculation

(Please note that though it does not say “Too” ambitious, you can purchase a sweatshirt that says AMBITIOUS via Phenomenal. And yes, I have one).

Until recently I would have told you that I wasn’t very ambitious.

For the first decade I spent in the trenches of motherhood, I had disassociated from that part of my identity. Having taken a step back in my career to raise my children, I couldn’t claim my ambitiousness because it didn’t align with what my life looked like. If I was ambitious, I wouldn’t be working part-time. If I was ambitious, motherhood wouldn’t have engulfed my life the way I allowed it to.

But I am an ambitious woman. I am now, I was before, and I think I always will be.

Most of my friends, family, and former co-workers are likely thinking, “No shit, sherlock.” When I worked as an editor at HarperCollins, I was always clamoring for promotions, credit, accolades, an office. One colleague said during a feedback session that I had “moxie.” During the nine years I worked there, I went from editorial assistant (low man on the totem pole) to senior editor. And had a baby.

Yet when I gave up that career in the face of the conflicting demands of motherhood, being ambitious felt incompatible with the life I had created for myself. I wanted to be the kind of mother who was always around, who was ever present at the playground, who envisioned lazy days at home building forts and reading books. But I didn’t realize that my ambition could not be buried. It would seep through the heavy denial I’d piled on top of it, begging to be acknowledged. Within the very days that I tried to content myself with childcare, I felt the call of creativity.

I tried to squash it. Lord knows I did. I tried to contain it during the 15-20 hours of dedicated work time I allotted myself. But it would not be contained. I wanted big things. So I tried to do big things but in a small amount of hours. During many of the years that I was ghostwriting books, I had no more than 20 hours of childcare a week. And yet I wrote 11 books during those eight years.

I don’t know how I did it.

I pretended that I was okay with this dividing of selves, this containment of my career into spaces that did not inconvenience my family too much.

But the truth is, that divided self is what caused so much stress, when there were so few boundaries between work self and caretaker self. I was constantly shifting, trying to answer an email at the park, or squeeze in a bit of editing during a gymnastics class. This is what we all faced during the pandemic, when all boundaries were erased and we constantly felt the need to be all things to all people AND were faced with the needs of the house at every moment of every day. Am I an employee or a mother or a maid or a cook or a teacher or a wife? Who the hell knows? How can I be all things to all people at all moments of the day? (Insert collective scream).

To be honest, there have been many times that I have daydreamed about being the kind of woman who could focus solely on the care of her children and the upkeep of her household. I know it is a full time job and has worth and value (actually, a lot of value according to the New York Times, just not our patriarchal society). Sometimes I want to be the woman whose lists of tasks for the day include grocery shopping, a Target run, signing up for those last few weeks of camps we’ve yet to secure, ticking off those forms I need to fill out for my daughter’s entry to middle school. Instead, I have all those things to do after I do enough work to feel like I’ve done enough for the day. (Yet when is it ever enough, when you are a writer? Sure, there are the words, which are finite, but the networking and submitting and expanding your platform and tweeting about your latest post, and commenting on the tweet of another writer in hopes they might follow you, that work feels never-ending. There is always more that could be done. I know that feeling is not unique to being a writer but encompasses most of our jobs today).

So often, it feels like it would be simpler if I could just be a mom. Although I admit this may not be true and is wishful thinking that there were some other path that wouldn’t leave me feeling so constantly pulled in a million directions.

But instead there is this yearning inside me to put my words out into the world and when I stifle them, thinking it is better to be silent, I feel like I want to scream.

So here I am, having just turned 42, and recognizing that I am an ambitious woman.

How had I become so blind to it?

When I was writing my piece that ended up in The Lily in July 2021, in an early draft I had written this phrase:

That is often the pressure women feel. That their career ambitions should take a back seat to their role as a mother. I don’t even have huge career ambitions, honestly. But I do know that I feel most like myself when I’m writing or working on books.

Every time I reread that phrase in my revisions: I don’t even have huge career ambitions, honestly… it didn’t feel right in my bones. It felt like a lie, even though I knew that when I wrote it, it felt true, that I believed it was true. But after the fourth or fifth reading, I finally admitted the truth. I am ambitious, and I do have big goals. How would I ever accomplish them if I couldn’t admit them to myself?

This is a side effect of turning forty. I have grown tired of bullshit, including my own.

As I began to unpack why I was so uncomfortable owning my ambition, I realized that subconsciously, I believed that to be ambitious was to be selfish. It was to want something for myself. It was to consider myself important. It was to admit that I would put myself first sometimes, maybe even often, so that I could accomplish my goals.

This is not how women have been raised. We tell them they can become anything they want, while simultaneously reminding them to take one for the team, accommodate others, give, sacrifice, and wait their turn.

Women have learned to temper their ambitions because we are told not to want too much. Much like we are supposed to stay small physically to be palatable to the world, we curb and deny our appetites in all kinds of spaces all the time.

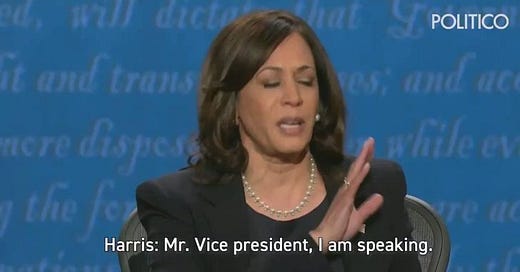

Even more, we temper our ambition because we are constantly put in positions where people question the value of our voice. It is why men interrupt us 33% more than when they are speaking to other men. It is why Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris have become icons for us (“nevertheless, she persisted”). Because underneath all of this is the misogynistic question: What could we have to add to the conversation?

Isn’t that our most audacious belief as women, that we might have something to offer the world? Our most subversive act to dare to value our own voice?

I understand why it is challenging to own our ambition. The messaging of motherhood is that ambition should die once we have the all-encompassing, all-fulfilling responsibility of our children (Jessica Valenti just wrote a searing challenge to this lie last week). Add to that the concrete evidence that some men find ambitious women threatening. In All the Rage: Mothers, Fathers and the Myth of Equal Partnership (an upsetting but validating read), Darcy Lockman writes:

“Studying the marriage and cohabitation histories of best actress and best actor nominees and winners from 1936-2010, researchers at the Johns Hopkins and University of Toronto business schools determined that after the award ceremony, best actress winners remained coupled for half the amount of time as those who were nominated but didn’t win - 4.3 years as opposed to 9.5 years. Best actor winners, in contrast, stayed in their relationships for an average of 12 years, the same as the actors who’d been nominated and lost. The study’s authors write, ‘[The] social norm for marital relationships is that a husband’s income and occupational status exceed his wife’s. Consistent with this norm, men may eschew partners whose intelligence and ambition exceed their own…’...

A woman who wins a political race finds herself in a similar position. Research in Sweden has found that for female candidates, winning a race for government office doubles the baseline risk of subsequent divorce; campaigning and then losing does not. Whether a male candidate wins or loses an election has no direct bearing on his marital future.”

I’m lucky to be married to a man who is not threatened by my ambition. However, my ambition is an inconvenience to us both. There is a reason why 70% of the top male-earners in the United States have a spouse who stays home. When women’s ambition means that we can no longer care for the house or the children in the way we used to or are expected to by society, it leads to conversations and negotiations that are far from easy (thus the existence of books such as Fair Play, Drop the Ball, and yes, All the Rage).

I do not write this to blame husbands but to illuminate the way patriarchal society prioritizes the work of the husband over that of the wife. Men have been conditioned to prioritize work, as that is what our society celebrates in men, and particularly father’s - their ability to provide. Thus men feel obligated to be available to their clients in the way that women have been conditioned to feel obligated to their children. This dynamic creates the tension that is found in so many heterosexual marriages today, where women, even if they are the primary breadwinner, still shoulder more of the childcare and household work.

Though very few men are as unlikeable as the protagonist Toby in Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman Is in Trouble, this line packs a punch:

“He might pretend he liked her bigness, but he couldn’t actually accommodate it into his life – he couldn’t bear what it took to be around someone whose obligations were as important and non-negotiable as his.”

This is the work in front of us. That we lay claim to the right to be ambitious, to stop apologizing for it or only allowing it if it doesn’t impact others. It may not be easy, but if we are ever going to accomplish gender equity, we have to stop stifling our ambitions. We have to dare to imagine what we have to offer the world, and then go after it, undeterred.

FURTHER READING

Women’s Work: A Personal Reckoning with Labor, Motherhood and Privilege by journalist Megan K. Stack. An excerpt:

“My time had been used as capital. It had been invested in the family future to improve our collective position….There is a lingering expectation that men will pay in money. But when it comes to time, it is almost always the woman who pays. And money is one thing, but time is life, and life is more.

How many ideas, how many discoveries, how much art lost because the woman spent her time somewhere else? How many ideas stillborn, how many inventions undone, how much original thought passed off quietly to a man so he can take credit – just not to waste, not to miscarry the idea, to pass it, one way or the other, into the world?”

What the Conversation about the “Great Resignation” Leaves Out by Meg Conley in Harper’s Bazaar

American Moms Are Being Gaslit by Jessica Valenti

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

“Was it her fault that she had bought into the popular societal myth that if a young woman merely secured a top-notch education she could then free herself from the historical constraints of motherhood, that if she simply had a career she could easily return to work after having a baby and sidestep the drudgery of previous generations, even though having a baby did not, in any way, represent a departure from work to which a woman might, theoretically, one day return. It actually, instead marked an immersion in work, an unimaginable weight of work, a multiplication of work exponential in its scope, staggering, so staggering, both physically and psychically (especially psychically), that even the most mentally well person might be brought to her knees beneath such a load, a load that pitted ambition against biology, careerism against instinct, that bade the modern mother be less of an animal in order to be happy, because – come on, now – we’re evolved and civilized, and, really, what is your problem? Pull it together. This is embarrassing.”

I feel every word of this in my bones.