In Praise of Becoming Unhinged

On the portal that opens in our forties, All Fours, and the power of no longer giving a f*&k

I have a new book I’m an evangelist for. In case you are wondering about my past favorites, they include Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder and Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner. And interestingly, this book felt like their cousin. Or sister. In any case, these books are most certainly related.

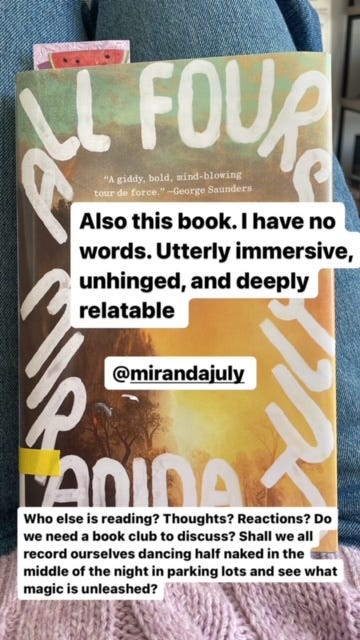

The book is All Fours by Miranda July.

I promise this will not be a post with spoilers because I want you to read the book and have your experience with it unvarnished by my interpretation. I honestly believe there is so much in this book that each reader will take from it what they need. Dealing with perimenopause? Its got you covered. Frustrated by the drudgery of heterosexual marriage? Yep. Got that, too. Struggling to reconcile yourself as a woman, mother, and artist? Nailed it. Plagued by a traumatizing birth experience? You’ll find solace here, too.

But what I want to talk about, and what it brings up most for me, is what happens when women want to escape their lives. Not forever. They don’t necessarily regret what their life has become. But they can’t pretend that all is well with them internally. They can’t just keep plodding away, dealing with the day-to-day-ness in the ways they did before. (Read my post on Internal Family Systems and how we don’t have to keep soldiering on below).

The first part of All Fours kept reminding me of Fleishman Is in Trouble. (If you haven’t read the book or watched the brilliant Hulu series starring none other than Claire Danes, what have you even been doing???) The narrator of All Fours is not being rational. In fact, some might even call her unhinged. Like Rachel Fleishman, who disappears one day, and her family cannot find her, and it isn’t intentional per se, she just can’t seem to remember what she should be doing, and thus her life devolves into a fever dream, this narrator has intentions to drive to New York City for work, and yet never even leaves the confines of LA. As you read, you don’t quite understand what is happening. And neither does the narrator. And yet, granted with two full weeks freed from her domestic responsibilities, wouldn’t anyone go slightly mad with the ability to finally do whatever they want? Like, yes, I can keep driving, or I can stop right here and have lunch. And I’m actually pretty tired, so I can pull over and stay at this motel. And this narrator somehow lives the next 14 days letting her whims, her desires, her irrational wants, guide her.

“The sudden absence of responsibility was a floaty, frothy, almost hallucinogenic weightlessness. No one to make breakfast for, no need to pack a five-part Bento Box lunch, no need to yell Put on your shoes! Brush your teeth!”

All Fours, Miranda July

But we must name the other important thing here. The age of this character. She is 45. And as many have noted, as Anne Helen Petersen has deftly explored in Are You In the Portal?, something happens to women in their forties.

They stop giving a fuck.

Why does this happen? No one really knows. But there is coterie of women in the novel who verify that this phase of life causes upheaval. It isn’t always bad. But it certainly is a time where things can get a bit…messy. Maybe this happens because a portal opens up which allows you access to a more true version of yourself. Perhaps it is due to the shucking of the good girl persona which we’ve learned to let guide us to survive in the world as a woman. Perhaps it comes because the demands of womanhood, motherhood, wifedom are getting heavy at this point in our lives and we can no longer withstand carrying them.

I recently listened to the first two episodes of Season Two of the podcast Mother Is a Question. Hosted by best friends Julia Metzger Traber and Tasha Haverty, this new season kicks off with a bang. It explores the story of Anne, who at age 40, left her three children. It wasn’t for forever. But she, upon divorcing her husband, had a chance to go on vacation to America with some friends. She spent ten days relaxing by the pool, going out to dinner, looking up at the vast stars of the desert. She says: I felt like I could breathe, laugh, and be free. I wasn’t answerable to anyone. And I just felt like I had a glimpse of who I was. I felt like that I saw….me. A person that I don’t think I knew. She was happy and fun.

When she returns from her vacation, she realizes she cannot just go back to the way it was. She wants to discover this self. She decides to return to America for as long as her visa allows her: 90 days. Then she’ll return and decide what to do.

I won’t give any spoilers, but we again witness the need, around the age of 40, to reset the terms. It’s like we wake up one day, and can finally see our lives as they are. And we becomes desperate to find our selves that have been lost along the way.

“Maybe midlife crises were just poorly marketed, maybe each one was profound and unique and it was only a few silly men in red convertibles that gave them a bad name. I imagined greeting such a man solemnly: I see you have reached a time of great questioning. God be with you, seeker.”

All Fours, Miranda July

As All Fours goes on, it continues to be really, really weird. And yet, in all the narrator's desperation and weirdness, I could also deeply relate. And this is when it began to remind me of another book I love, Nightbitch. In fact, I wondered… is this narrator Nightbitch, just five years later?

If you haven’t read Nightbitch (again, what exactly have you been doing???), it is another unnamed narrator. She has given up her artist career to tend to her toddler. The book captures the mundanity of toddler care in a way nothing else does. And this narrator also gets a bit… unhinged. She believes she is turning into a dog. And at night, this dog self goes out wandering.

When you read descriptions of the book, you feel like: how on earth could that work? And yet it does. On a deep visceral level.

“She likes the idea of being a dog, because she can bark and snarl and not have to justify it. She can run free if she wants. She can be a body and instinct and urge. She can be hunger and rage, thirst and fear, nothing more. She can revert to a pure, throbbing state.”

Nightbitch, Rachel Yoder

So as I think about these books and these characters and these trajectories, I wonder: is being unhinged actually something desirable? I know, the definition is not very positive. Highly disturbed, unstable, distraught. Affected with madness or insanity.

And yet, let’s consider the definition of hinged: attached or joined with a hinge. And I think it is exactly this “hinged-ness” that women struggle against in mid-life. We are tired of being so damned connected to others. Our spouses, our children, our kin. We want to “un-hinge” and see what it feels like to just be alone. On our own. “I was not answerable to anyone,” as Anne says.

This is the only way we can really access what we truly want, when we’ve untethered from the concerns of others. Not just from our spouses, but from those children, or families of origin, or bosses who expect too much, or from society that demands perfection. We have to go a bit crazy to allow ourselves to fully shed the fears of - what will they think?

Then we can come back down. I’m not saying we need to be unhinged forever. But what if, just for a time, being unhinged was what we all needed to be?

“This was the thinking that had kept every woman from her greatness. There did not have to be an answer to the question why; everything important started out mysterious and this mystery was like a great sea you had to be brave enough to cross. How many times had I turned back at the first ripple of self-doubt? You had to withstand a profound sense of wrongness if you ever wanted to get somewhere new. So far each thing I had done in Monrovia was guided by a version of me that had never been in charge before.”

All Fours, Miranda July

I would like an All Fours book club. Excellent essay!

Yes yes yes.